Holy Week Madrid

“In a little while, I felt stronger, and put out my hand for the matches. I groped about, for a few moments, blindly; then my hands lit upon them, and I struck a light, and looked confusedly around. All about me, I saw the old, familiar things. And there I sat, full of dazed wonders, until the flame of the match burnt my finger, and I dropped it; while a hasty expression of pain and anger, escaped my lips, surprising me with the sound of my own voice.”

Excerpt From: William Hope Hodgson. “The House on the Borderland”.

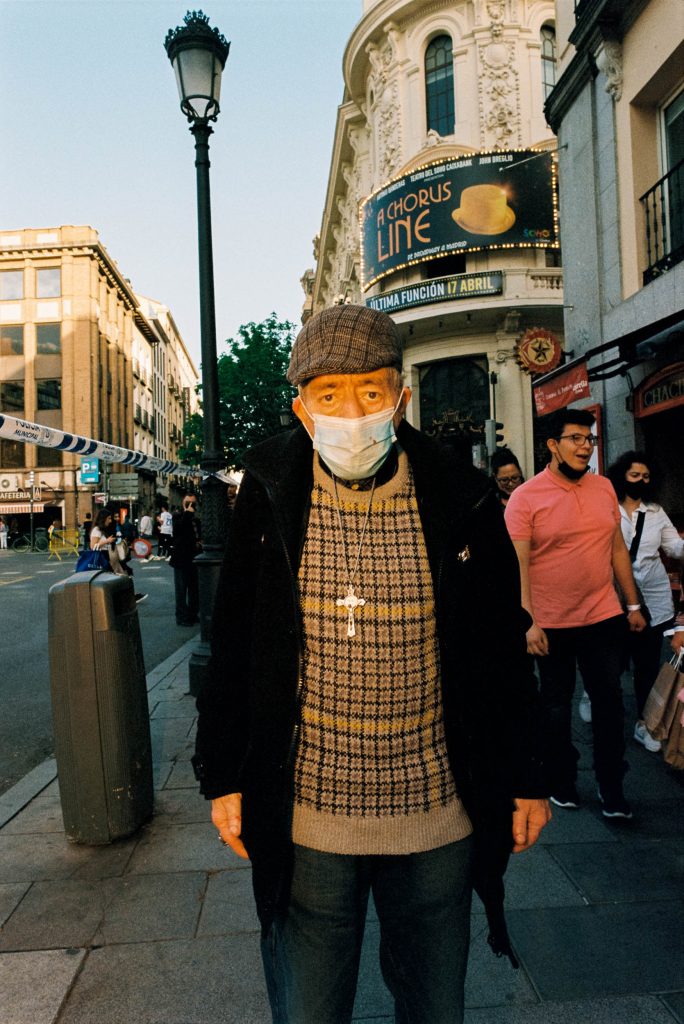

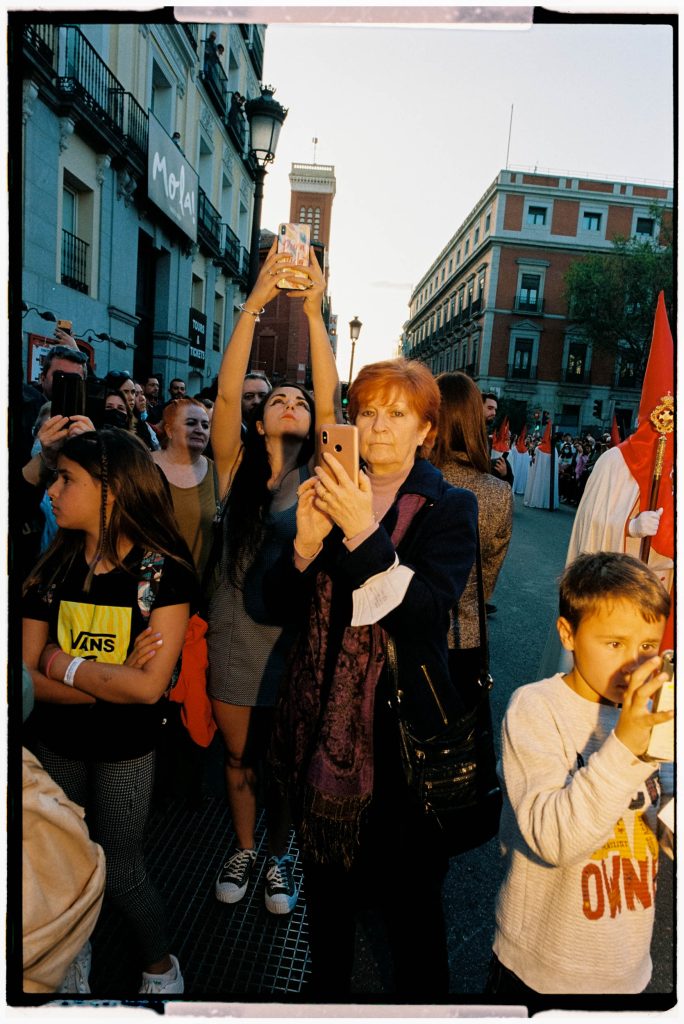

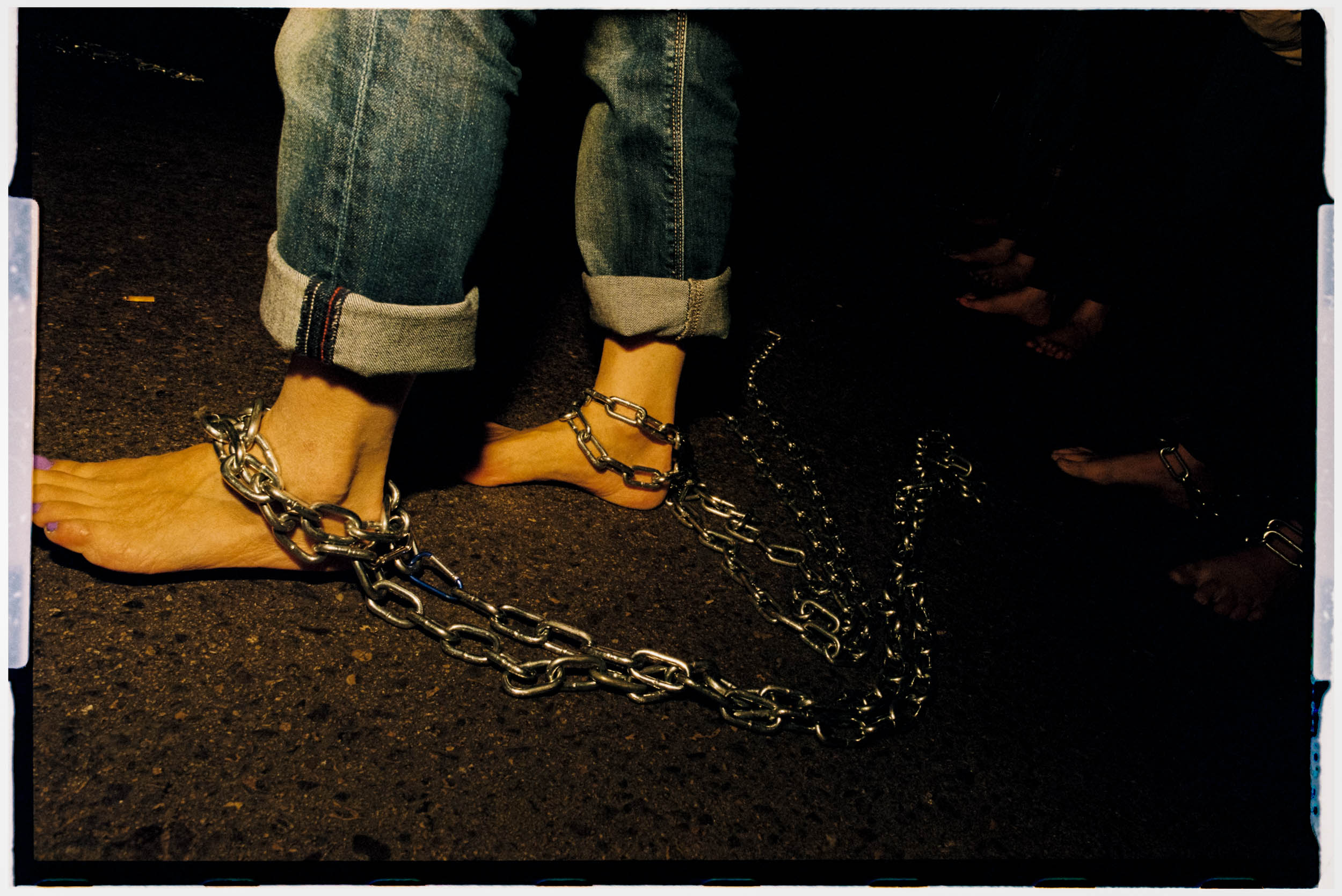

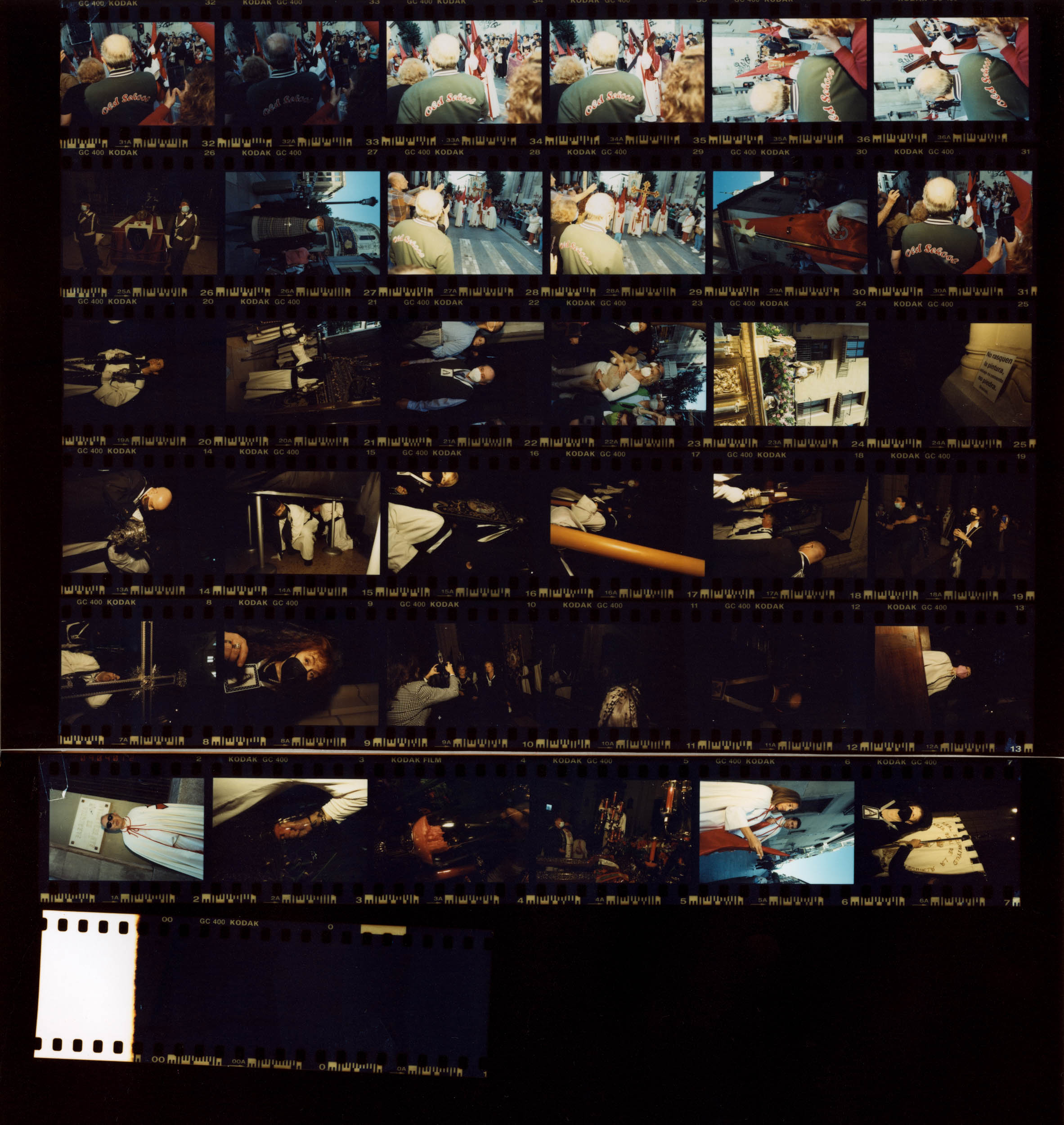

April 2022, final moments of the COVID-19 era: for two years, there had been no Holy Week processions in Madrid – the most striking mass events of Spanish Christian liturgy. Thousands if not millions of people crowd together on the streets to watch devotees parading past, carrying heavy pasos (sculptural representations of Virgin Mary or Jesus, weighing as much as your average car) on their backs. They are preceded and followed by other believers wearing strange ritual attire, their feet in chains, carrying a cross upon their shoulders, with music and chanting to accompany this display of their faith. What would the return of those days of celebration and religious expression look like in 2022 Madrid?

Even though I had lived in the Spanish capital for most of my life, I had very rarely been in direct contact with Christian rituals, Holy Week processions included. I had always been drawn to them, but had never taken part in them for longer than 20 minutes.

Perhaps it was a desire to keep my body in that dreary tension that, due to COVID, loomed over us every day in 2020-2022 that made me hit the streets of Madrid and submerge myself in the festival, which brings together the darkest and most tragic side of religious narrative with the devotees’ displays of love and joy.

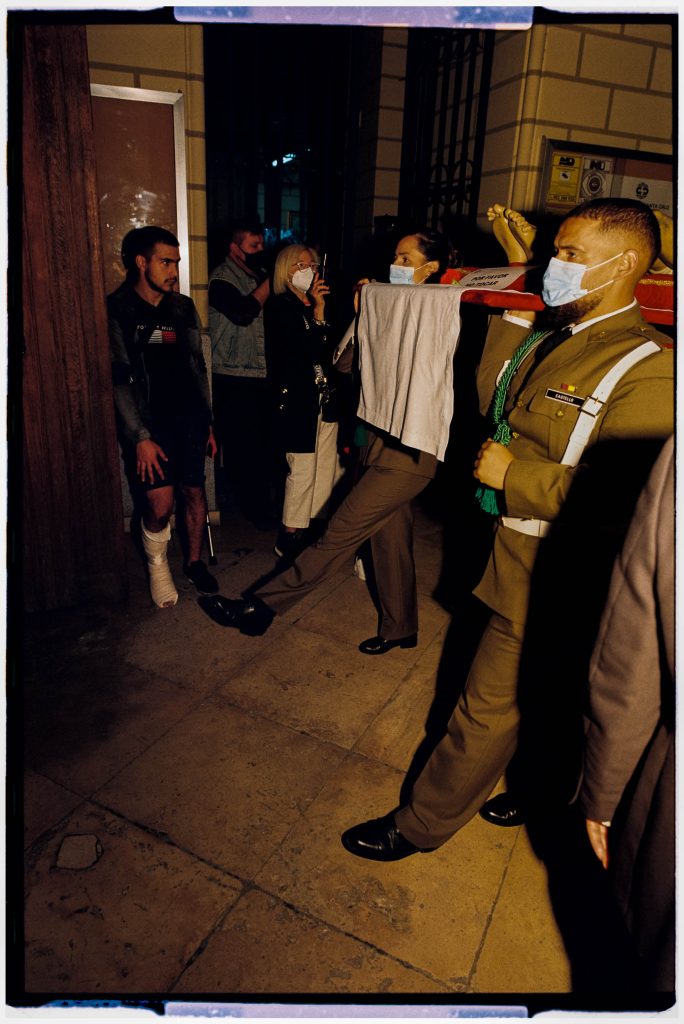

Under the light of day, I felt peaceful and curious, as if walking among literary characters, while I listened to faithful words and observed people’s emotions. No doubt, I was out of my comfort zone, but also calm in a pleasant and festive environment. In the shadows of churches and after nightfall, it was a different story: watching all those covered faces, where only the eyes moved, sunken as they were within pointed fabric hats, all those hands carrying staffs or altar candles, it all, inevitably, cast a shadow over my mood.

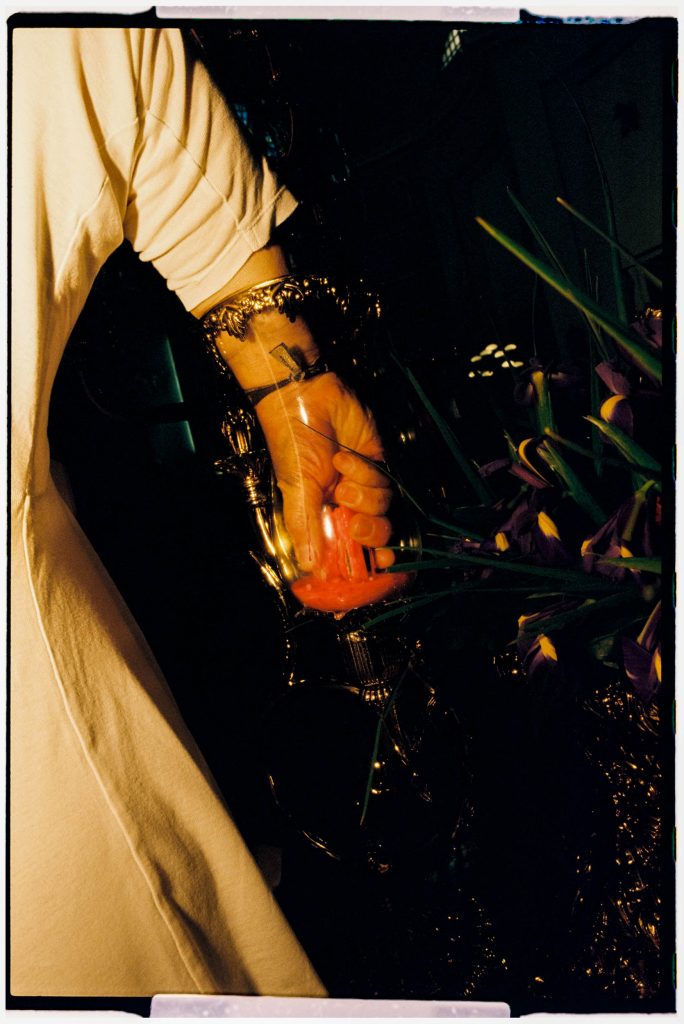

As the afternoon advanced and the night came, fatigue, the heaviness of the bodies under the pasos, the onlookers’ faces, the regular rhythm of footsteps, everything became increasingly solemn, and some sort of sorrow overtook me. Shooting with my flash felt like lighting a match that threw light on my surroundings and my spirits for just a few thousandths of a second. The presence of light, so important for these traditions, connected to divine love, was conspicuous by its absence, limited as it was to some altar candles here and there and the medium intensity of street lights under which the processions passed. After every flash, the dark returned, and my mood sunk further.

It might have been that the health situation still required us to wear masks and that the general COVID-time spirit was still in the air, but I expected to find something gloomier than usual. True, the times we were living through could be read on people’s expressions and on their faces, covered by blue or white, but compared to the oppression one feels when watching shackled people walking barefoot on asphalt, masks or expressions of concern had a minimal visual impact.

I took one last look around: although everyone seemed quite pleased, they also carried a weight upon their soul which could not be removed from their faces, mask or no mask. Once a certain degree of gloom is reached, it is hard to move beyond.

I had just experienced my first full day of Spanish processions and, after switching off my flash, I carried the dark with me all the way home.